Pretend, if you can, that the last week didn’t happen (a tall order for the Stratechery demographic, I know), and imagine another scenario: China invades Taiwan. What happens then?

I’m not a military expert, but my assumption is that China would be successful; the biggest unknown variable would be time. If the U.S. does not intervene the conflict would be shorter; if the U.S. does the conflict would be longer, and ultimately be decided in the way that wars are always decided: through industrial capacity and logistics. China has a meaningful advantage in both areas given its relative manufacturing might and the fact the conflict would happen off their coast.

There are experts who disagree; the Center for Strategic & International Studies ran a series of wargames in 2023, and concluded that the U.S. and its allies would repel a Chinese invasion, but at a heavy cost to U.S. military forces and Taiwan generally. That, however, raises a more pertinent point: when it comes to the economic impact it hardly matters who wins or loses. In both cases China is effectively removed from global supply chains, and Taiwan’s economic output — including chips from TSMC and others — is destroyed.

It’s difficult to overstate the extent to which every aspect of modern life rests on global supply chains, which are so long and complex that no one can truly understand the effects of messing with them. It has, however, gotten easier to grasp the complexity in recent years: first there was the bungled economic response to COVID, where a temporal interruption in supply chains triggered worldwide supply shortages and contributed to global inflation; then there was last week, when the shock of blanket tariffs from the Trump administration led to a meltdown in worldwide stock markets that seems to still be ongoing. A war over Taiwan, however, would put all of these to shame.

Last November, in the wake of President Trump’s second election, I wrote A Chance to Build: that title referenced the optimistic conclusion to a piece that was, if you read closely, a pretty pessimistic summary of the current trade situation, with a special focus on tech. To summarize:

- The U.S. leveraged foreign aid, direct investment, and its consumer market to rebuild Europe and Japan after World War 2, and pegged currencies to the U.S. dollar (which was pegged to gold) to do it. This started the cycle of foreign countries exporting to the U.S. and buying U.S. debt with the proceeds, although the U.S.’s relative size to the rest of the world meant that the U.S. still ran a trade surplus (the aid and direct investment were often used to buy U.S.-produced products).

- By 1971 this system was about to collapse under its own weight, leading the U.S. to de-peg from gold (i.e. depreciate the U.S. dollar) and dissolve the Bretton Woods system of currency controls. This led to a decade of pain — including the oil shock of the 1970s — but what emerged had a similar structure to the post World War 2 system, just with the U.S. dollar as the reserve currency, untethered from gold. This meant there was inelastic demand for U.S. treasuries, which basically made it impossible for the U.S. to not run a deficit, either in terms of trade or the federal budget. Still, this was maintainable given the relative size of the U.S. economy to its trading partners.

- What changed in the last 25 years was the entrance of China into this system. China — clearly in retrospect, although perhaps predictably for those who understood China historically, beyond its backwardness over the previous two centuries — had far more capacity than the system could bear. It’s not an accident that U.S. deficits — both in terms of trade and the federal budget — have exploded in line with Chinese growth.

China is the skeleton key to understand so many oddities about the U.S.’s fiscal situation over the last fifteen years in particular, especially how it is that the U.S.’s response to the Great Recession didn’t lead to inflation: Chinese production was deflationary, and their ever-expanding trade surpluses created an ever-expanding market for U.S. debt, whether it be held by the Chinese national government, provincial governments, state-owned enterprises, etc. This inelastic demand also served to keep the dollar artificially high, in defiance of the theoretical-expected response to long-running trade deficits.

This, more than anything else, is what has hollowed out U.S. manufacturing. The cost of cheap consumer goods and a seeming inexhaustible capacity for U.S. debt was the shifting of ever more manufacturing abroad. Yes, things like lower costs and different labor standards played a role, but it’s the structure of the world economy that matters most; indeed, China’s labor costs are significantly higher than they used to be, but China’s manufacturing dominance is actually accelerating.

Part of this is due to China’s decision over the last few years to respond to the puncturing of its housing bubble by pushing resources into export-oriented industries; another part is the unfortunate reality — under-appreciated by apostles of comparative advantage — that capabilities compound. I wrote in that Article:

The story to me seems straightforward: the big loser in the post World War 2 reconfiguration I described above was the American worker; yes, we have all of those service jobs, but what we have much less of are traditional manufacturing jobs. What happened to chips in the 1960s happened to manufacturing of all kinds over the ensuing decades. Countries like China started with labor cost advantages, and, over time, moved up learning curves that the U.S. dismantled; that is how you end up with this from Walter Isaacson in his Steve Jobs biography about a dinner with then-President Obama:

When Jobs’s turn came, he stressed the need for more trained engineers and suggested that any foreign students who earned an engineering degree in the United States should be given a visa to stay in the country. Obama said that could be done only in the context of the “Dream Act,” which would allow illegal aliens who arrived as minors and finished high school to become legal residents — something that the Republicans had blocked. Jobs found this an annoying example of how politics can lead to paralysis. “The president is very smart, but he kept explaining to us reasons why things can’t get done,” he recalled. “It infuriates me.”

Jobs went on to urge that a way be found to train more American engineers. Apple had 700,000 factory workers employed in China, he said, and that was because it needed 30,000 engineers on-site to support those workers. “You can’t find that many in America to hire,” he said. These factory engineers did not have to be PhDs or geniuses; they simply needed to have basic engineering skills for manufacturing. Tech schools, community colleges, or trade schools could train them. “If you could educate these engineers,” he said, “we could move more manufacturing plants here.” The argument made a strong impression on the president. Two or three times over the next month he told his aides, “We’ve got to find ways to train those 30,000 manufacturing engineers that Jobs told us about.”

I think that Jobs had cause-and-effect backwards: there are not 30,000 manufacturing engineers in the U.S. because there are not 30,000 manufacturing engineering jobs to be filled. That is because the structure of the world economy — choices made starting with Bretton Woods in particular, and cemented by the removal of tariffs over time — made them nonviable. Say what you will about the viability or wisdom of Trump’s tariffs, the motivation — to undo eighty years of structural changes — is pretty straightforward!

The other thing about Jobs’ answer is how ultimately self-serving it was. This is not to say it was wrong: Apple could not only not manufacture an iPhone in the U.S. because of cost, it also can’t do so because of capability; that capability is downstream of an ecosystem that has developed in Asia and a long learning curve that China has traveled and that the U.S. has abandoned. Ultimately, though, the benefit to Apple has been profound: the company has the best supply chain in the world, centered in China, that gives it the capability to build computers on an unimaginable scale with maximum quality for not that much money at all.

That line about Trump’s motivation looms large after the last week; the observation about Apple’s benefits looks much more precarious.

There is a fascinating history of the Nixon administration’s deliberations over closing the gold window, instituting price controls, and imposing a 10% import tax — the actions that effectively ended Bretton Woods — in this 2011 Article in Bloomberg Businessweek. What is interesting is that the decision was made under intense economic pressure, but the presentation was a PR masterpiece:

[Treasury Secretary John] Connally brilliantly packaged the program not as America abandoning its commitment to the gold standard but as America taking charge. He turned the dollar’s collapse, which could have appeared shameful, into a moment of hubris. The emphasis would be on righting America’s trade balance, as well as minor points such as a 5 percent cut in foreign aid. An aide to William P. Rogers, the Secretary of State, called and interjected, “You can’t cut foreign aid.” Connally said, “Tell him if he doesn’t shut up we’ll make the cuts 15 percent.” Shultz muzzled his disquiet over price controls; even Burns joined ranks. The group feverishly debated whether Nixon should address the country on Sunday night, which would mean preempting the popular Gunsmoke. The public relations aspect was paramount. Stein wrote later that the discussion at Camp David assumed “the attitude of scriptwriters preparing a TV special.” No one pretended to know how controls would work; the question was scarcely debated.

Addressing the nation on Sunday, Nixon blamed currency speculators and “unfair” exchange rates rather than U.S. monetary policy. Politically, he hit the jackpot. Monday’s nearly 33-point rise in the Dow was the biggest ever to that point. Nixon’s “New Economic Policy” drew raves from the press. “We unhesitatingly applaud the boldness with which the President has moved,” read the New York Times editorial. In the present era, America’s inability to repair its fiscal problems has tarnished its credibility and hampered its currency negotiations with China. The Nixon Shock showed the U.S. taking action.

The end of Bretton Woods was probably inescapable, but it’s worth pointing out that the Nixon Shock was an economic disaster: the country endured a decade of drastic inflation that was only cured with sky-high interest rates and a massive recession (the architect of that cure, Paul Volcker, was a part of the team that instituted the Nixon Shock in the first place; Volcker came to regret it). In other words, the reaction of the market and the press was totally wrong.

The question is if what happened this last week ought to be compared to the Nixon Shock, or contrasted? Certainly the reaction is a contrast: everyone hates the “Liberation Day” tariffs, including the market. Moreover, the Trump administration’s rollout has been the very opposite of a PR masterpiece: no one in the administration can seem to agree about what exactly the goal is, or what success looks like. I’m certainly not going to attempt to speak for an administration that can’t speak for itself, particularly given Trump’s on-again-off-again approach to tariffs over the last few months.

What I do come back to, however, is what I opened with: there is a scenario within the realm of possibilities that is far more painful than anything Trump proposed; is it better to try and force into place a new economic system that, at least in theory, reduces dependency on China and resuscitates U.S. manufacturing now, instead of waiting for the current system to collapse by literal force? This does seem to be the administration’s goal: simply tariffing China is deadweight loss, leading to rerouting and the fundamental problem of the dollar as reserve currency unaddressed; blanket tariffs, on the other hand, are a valid, if extremely blunt and inefficient, way to meaningfully restructure incentives.1

Moreover, even if an invasion never happens, is the current system sustainable, fiscally or societally? Trump’s political success is, in many respects, the clearest manifestation of what happens in a system that pushes the gains to the globalized top while buying off the localized masses with cheap trinkets.

Ultimately, I actually think there is an important distinction between these downside scenarios, and it explains why I think that Trump’s approach, while more theoretically valid than it is being given credit for, is the wrong one.

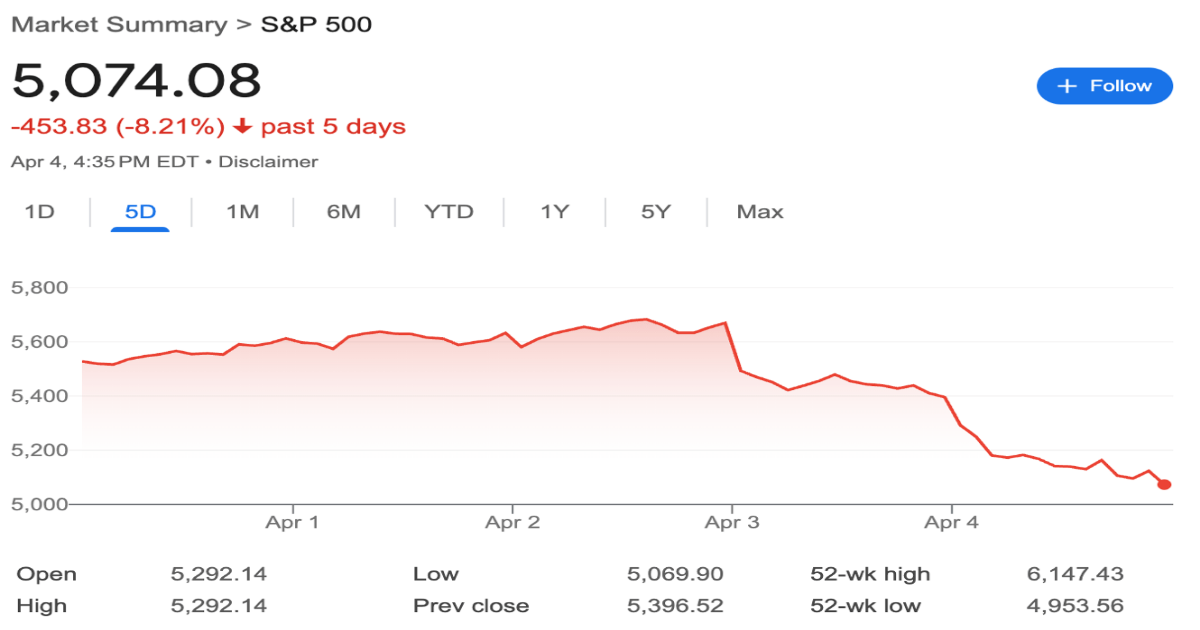

First, I’m skeptical that we have the stomach for what would be necessary to remake the global economic order. I might have had to spend a few paragraphs explaining this point previously, but I think a stock market chart speaks for itself:

I will note, by the way, that these losses aren’t entirely irrational or panic-driven: reduced trade absolutely hurts U.S. multinationals; one point that is being missed — at least until what happened in foreign stock markets this morning — is that it hurts foreign companies even more. No one wins in a trade war.

Second, the current economic system, flawed though we may now recognize it to be, is a complex system, built up over decades; one ought to be very wary in remaking complex systems in a top-down manner. It’s one thing to diagnose problems; it’s a very different thing to solve them. There’s a reason that new economic systems usually arise after major wars; it’s easier to build something new after the old thing has been destroyed (and there is the stomach for it, because there is no other choice).

Third, there are a lot of other things the Trump administration could be doing, particularly in terms of relieving regulation, ensuring equal opportunity throughout the economy, etc. It seems like a missed opportunity to be burning political capital on deficit reduction and trade rebalancing when there are major pro-growth opportunities still available. This seems particularly pertinent given the rise of AI, which has very high variance in terms of potential outcomes.

Make no mistake, the structural problems facing U.S. manufacturing in particular are very real, and the China-Taiwan systemic risk is only going to increase. Instead of changing the system to ameliorate the risk, however you could simply address the risk directly; I think the best way to do that is to undo the chip controls and tie China even more tightly into the current system generally, and to Taiwan specifically. Yes, this is kicking the can down the road, but path dependency is a far more powerful force than we often realize.

To go back to the Nixon Shock, I think one reason why it was a PR success is because the crisis was inescapable; I wonder if one reason why “liberation day” is a PR disaster is because there is still more road to kick the can down.

So what of tech companies, and the benefits that companies like Apple have gotten from Asia generally and China specifically?

First, it is worth articulating this benefit in full. Steve Jobs, in his first tenure at Apple, was deeply committed to manufacturing, including building a futuristic factory in Fremont for the Mac; that merely cost the company millions — his attempt to do the same for NeXT all but drove the company out of business. What Apple needed — and eventually found in China, under Tim Cook — was scalability: Apple would focus its integration chops on getting the product right, and trust contract manufacturers to achieve the flexibility of meeting demand. This, more broadly, is an important addition to the capability discussion above: manufacturing has changed from being a point of integration with a product to being a horizontal scalable services offering; developing the customer service chops necessary for such a business would be a significant cultural challenge for a new U.S. manufacturing base, a la Intel’s struggles to become a foundry.

To that end, one benefit of a war over Taiwan is that it would be so terrible for tech companies that there really isn’t much benefit in planning for it; the hedging cost — which would entail building out these scalable horizontal service providers, which for economic reasons must serve more than one company or product — would be so astronomical that it probably wouldn’t be economical to do anything other than deepen the status quo, particularly given that the status quo contains strong incentives for all parties, including China, to avoid disaster.

These tariffs, however, are much more complicated, because they exist (for now anyways), while a war does not. Apple, which has so adroitly balanced the relationship with both the U.S. and Chinese governments, is obviously the most impacted: you can quibble with the Wall Street Journal’s estimates on the tariff impact on an iPhone, but it certainly is directionally correct that Apple will probably face little choice but to substantially raise prices. That has the direct problem of leading to fewer sales (even if iPhone demand is probably fairly inelastic), and the secondary problem of decreasing the market for Apple’s services business, it’s primary source of growth.

There’s an even more disappointing knock-on effect: Apple’s services business is not subject to tariffs, which is to say it will become even more important to Apple’s bottom line; that decreases the likelihood that Apple transforms its relationship with developers, which I think is its most promising opportunity with AI.

All of the advertising-based businesses — Meta, Google, and Amazon — will also be negatively impacted. Lots of cheap products means lots of advertising (and lots of products on Amazon specifically), much of which could disappear; could this mean a return of app install advertising, if e-commerce advertising decreases, lowering prices overall? All three companies also source hardware from China, both for sale to consumers and for their data centers. It’s Microsoft and its old formula of software and distribution that may be the most shielded. Of course it needs data center hardware as well, and more expensive PCs means less Windows revenue, but the world of bits has never seemed more attractive relative to atoms.

The problem for all of them, however, is the same problem faced by the economy generally: more grist in the wheels of the economy means lower velocity, and lower velocity is bad for tech companies in particular. These are entities who are predicated on Aggregating unfathomable levels of demand in order to gain leverage on massive up-front costs; now demand will slow even as the costs rise. Moreover, their regulatory risk will likely increase: one way for entities like European countries to retaliate will be to simply ramp up the fines, or figure out a way to tax software services, further slowing velocity; the worst case scenario would be a dedicated effort to break away from U.S. tech completely. I think this is unlikely, but more likely than it was a week ago.

So what of my optimistic spin last November, when I called my tariff preview A Chance to Build? Well, my skepticism is keeping with the pessimism embedded in that piece: it’s a lot easier to build from scratch than to retrofit something that exists; that applies to companies just as much as countries and economic orders. I’ll be cheering for the startups that seize this opportunity; I’m sympathetic to the incumbents looking at guaranteed costs with very uncertain rewards.